ON A nature strip flanking the Carlton General Cemetery, just a short walk south of the old Carlton ground, stands a mighty river red gum.

Thought to be at least 300 years in age, the cream-coloured limbs and lance-shaped leaves of this vast native tree touch the skies over Princes Park Drive.

Closer to terra firma, the tree’s gnarled old trunk and rough bark slabs still bear a tell-tale scar from another time, when the men, women and children of the Wurundjeri freely roamed.

“In our language we call the red gum ‘beyal’ – that’s the Woi wurrung name for red gum,” says Wurundjeri Woi wurrung Elder Uncle Bill Nicholson as he stands beneath its grey-green canopy.

“Looking at the scar in the tree itself it’s a large, long scar with quite a lot of years of growth around the outer edges, which tells me it’s quite old. The scar indicates that the bark taken would have been fired into shape and used for a ‘koorong’ or canoe – a flat-based canoe used almost like a gondola, which would have been paddled out into the wetlands that would have been around before the sporting fields of Carlton here.

“The redgums like this one are telling me this, because they need to be inundated with water.”

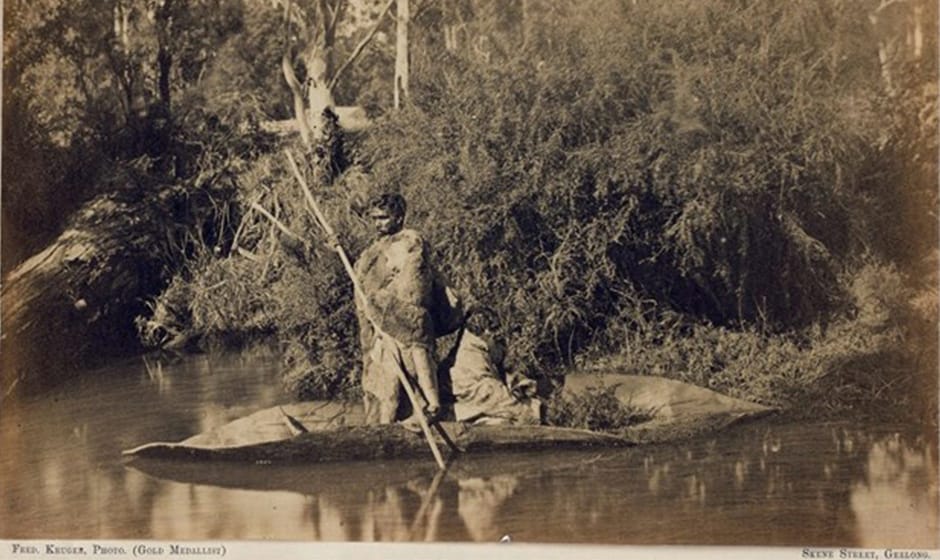

Aboriginal men and bark canoe. This photograph, captured by Fred Kruger, is thought to have been taken on Badger Creek, at Coranderrk, near Healesville, in 1870. Image courtesy the State Library of Victoria and the Elders of the Wurundjeri Tribe Land & Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Incorporated

Aboriginal men and bark canoe. This photograph, captured by Fred Kruger, is thought to have been taken on Badger Creek, at Coranderrk, near Healesville, in 1870. Image courtesy the State Library of Victoria and the Elders of the Wurundjeri Tribe Land & Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Incorporated

Nicholson has taken this correspondent on a very special journey, to a time and place pre-dating 1835 when European settlers on horseback followed the Indigenous trade and travel routes, known as ‘songlines’ – named so because navigational instructions, geographic features and man-made route markers were coded in song sung by the Indigenous as they travelled.

As with so many other areas of Melbourne, Carlton itself carries a number of traditional songlines of which most people have been unaware. The ground itself lies by a significant songline whose origins can be found at the Williams Creek tributary which once flowed down Elizabeth Street to join the Yarra. The songline followed the ridge along William street, past the law courts, along Peel Street and the Victoria Market, then up Royal Parade to Sydney Road and the Hume Highway, all the way to Sydney.

In truth, Carlton and its surrounds remain a junction for all the major songlines heading north and west out of Melbourne. For instance, the Royal Melbourne Hospital/Royal Parade-Sydney Road songline later splits, with the first songline heading northeast along St George’s Road and later Plenty Road beyond the Merri Creek; and the second songline heading more easterly along Queen’s Parade to Heidelberg Road over the Merri.

Nicholson reveals that tribes and clans of the Kulin Nation utilised these songlines to meet on occasions of plenty in spring and late summer, and that the area now home to the Carlton Football Club and the University of Melbourne served an extremely important purpose for these meetings.

“The whole area had for hundreds of years been cleared by fire so that trees only remained at 25-metre distances, and the green mass of ankle-deep grass served as a huge kangaroo farm without any fences – which in turn provided a ready larder for the assembled tribes.”

The earliest presence of European settlement in the Carlton area was noted by the then Football Club Secretary Harry Bell, a co-author of the tome ‘The Carlton Story’, first published in 1958.

One of Bell’s entries states:

“It is interesting to note here that years before the introduction of Australian Rules football, Mr. John Oliver, who was a native of Roxburghshire, Scotland, arrived in Melbourne in 1839, and engaged in sheep grazing on the banks of the Yarra River, and during the time his homestead was where the present ‘Princes Oval’ stands.

“Subsequently, Mr. Oliver discovered Lake Hynam (South Australia) and settled there, where his partner was murdered, and where Mr. Oliver was killed in an encounter with a bushranger.”

Uncle Bill Nicholson by the old river gum, Carlton North.

The 97-acre Carlton park originally formed part of a 2650-acre site which, in 1845, was touted as a reservation for recreational purposes by Lieutenant Governor Charles Latrobe. It was so proclaimed in 1854 and reserved in 1873.

It is a matter of record that the Carlton Football Club fielded its first team on a clearing at Royal Park, where river gums like the one on Royal Park Drive proudly stood.

Sadly, the original inhabitants of the land paid the price. To quote Nicholson: “When the Europeans arrived, our peoples’ skill and expertise with bark removal were utilised as slave labour for the bark huts and bark buildings in the early days of Melbourne”.

Nicholson reminds that as a Wurundjeri Woi wurrung Elder and educator he doesn’t need to be told his Ancestors were here long before Carlton, long before Oliver and long before John Batman.

As he says: “I know”.

But for those of us who are non-Indigenous, the old river red gum with its deep, elongated scar, remains a living, breathing representation of a time when the Wurundjeri people freely roamed.

“This tree was cut with a greenstone axe, quarried about 120ks to the north, at a place we call ‘Willamoring’ – ‘Home of the Axe’ – near Lancefield, which is a sacred ancestral place. The axes have been quarried there for tens of thousands of years,” Nicholson says.

“The scar found on the side of this tree faces northeast, which is protected from the sunrise and sunset.

“It’s a classic example of our people’s understanding that if you were to destroy a tree by taking its bark — cutting the bark — you’re not only taking the natural habitat of birds and possums which are part of your food resources, but the future use of the bark itself . . . and I’ve seen a scar tree with three different canoes cut out of it.”