A tick over two years ago, a story appeared here about the life of Alf Egan. Egan, who was also known as 'Tom', is forever remembered as Carlton’s first known Indigenous footballer to lace a boot.

Listed as this club’s 478th senior player since 1897, Egan completed his senior debut, against Essendon, at Princes Park in Round 3, 1931. Named on a half-forward flank alongside another first-gamer Bernie O’Brien, Egan would boot a goal in the first of his 36 games for the Blues through the course of three seasons as a ruckman/forward.

Egan’s stoic display at centre half-forward in the 1932 Grand Final earned him universal acclaim. Alas, his time at Princes Park ended just a year later, with Carlton’s loss to Geelong in the first semi-final of 1933.

At 23, Egan saw fit to follow his football dream to North Melbourne, but by the end of ’35 and after just 15 senior appearances it was all over for him at League level.

While the previous article shed precious light on Egan’s hometown of Myamyn in Victoria’s south-west, little was recorded of his later years – other than that he was known to have fathered a son to a Richmond woman in the 1950s.

A labourer by profession, Egan of no fixed address would sadly succumb to heart disease at the age of just 51, with his cremated remains placed in a compartment of the Church of England section at Springvale Botanical Cemetery in January 1962.

The article of 2014 concluded with a plea to any of Egan’s descendants to make contact to help fill in the gaps.

Recently, one of them did – Egan’s son the much-respected Aboriginal elder Ted Lovett, himself a former Fitzroy footballer, who played two games on permit with the Lions in 1963 and a further seven in ’64.

"I've had a tough life but I've got through it". Ted Lovett, 2016 (Photo: Supplied)

Ted is proud of the fact that Egan is remembered as Carlton’s first Indigenous player and that he played League football before Doug Nicholls. Here, he reflects on the life of a father he never really knew and at 75, ponders his own incredible life’s journey, the great capacity to prevail and the triumph of the spirit.

I didn’t know much about “Tom” down home, but I have a handwritten book about the Egans. I know that Dad lost his uncle Bill in the Battle of the Somme. I also know that his big brother Mick served in New Guinea during the Second World War, and his younger brother Wilkie died of natural causes in Richmond.

The Egans and the Lovetts were first cousins and my grandfather was brought up strict Church of England. My younger sister Georgina was the only family member to get the Egan name on her birth certificate, and she was born after grandfather had died.

All our mob were Gunditjmara – “The Fighting Maras” as they called us. Football was our natural game and we used to kick a possum skin stuffed with charcoal.

My Mum ('Gertie') and Dad met in Heywood, but I was born in Carlton and most of us were born in Melbourne. We had a stepbrother who died, but we never knew him and still don’t know anything about him.

I had an older brother Victor who became a professional boxer, Tommy (who was a better footballer than me), Dorothy (a tomboy who could also play footy), me and Georgina. We were all taught how to look after ourselves because there was a lot of racism around.

Tommy and Dorothy have all since died and they died in that order. Now there’s only me and Georgina left, I’m 75 and she’s 73.

We all lived with Mum at 85 Young Street, Fitzroy (it’s housing commission now) and Dad lived with his family at 90 Somerset Street, Richmond. We’d catch the tram there and get off near the Skipping Girl. They lived a few blocks up on the right.

They weren’t happy times in Fitzroy because we more or less lived in poverty there. There’s a clipping from The Sun going back years ago of the five of us – all my brothers and sisters, and Mum living in poverty.

Later on, I worked in Aboriginal Affairs in the early days of the movement, the radical times. That was in the ’70s, with all the marches, and I did a lot for the Aboriginal people. I received the Centenary Medal for services to the Ballarat Aboriginal community.

I was about 15 years old when my Mum died of leukemia. My brothers and sisters were all there the night she died at St Vincent’s Hospital. My Dad died in sad circumstances in Burnley in 1962 and I’d say I was about 20 at the time.

Dad didn’t really have anything to do with us in those early years and after a while I was made a state ward, but through no fault of the family. I went to Mildura fruit picking and me and an Italian boy got hauled in by the police for walking the streets. We were rounded up on the Friday night and went to court on the Monday. The Italian boy went home with his mother and I was made a state ward – and I had eight years of institutionalisation – Royal Park, Turana and the Salvation Army Boys’ Home.

In the end, I worked for the department that made me a ward of the state.

I never really played junior football, because from the time I was 14 I played seniors. Funny thing, Charlie Sutton wanted me and Tommy to go to Footscray as we’d previously played out at Brooklyn, but Tommy was mad Fitzroy and so we stayed put.

I played nine games for Fitzroy, but I had a few problems with my colour. I had natural ability – I played anywhere, sometimes full-forward, but mainly wing, half-forward or halfback. Playing for North Ballarat later on, I won the Henderson Medal in 1963 and ’65 – the first person to win the Ballarat League’s best and fairest award twice.

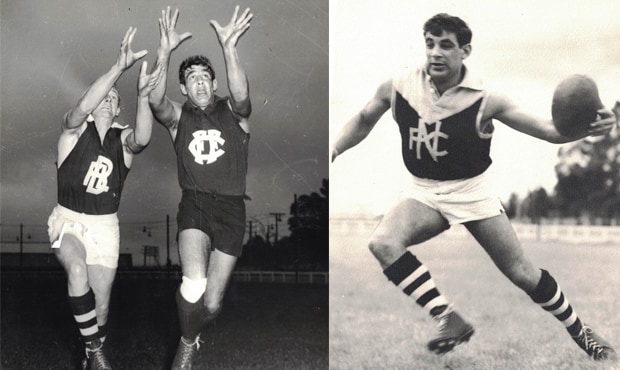

(Left)Ted Lovett, in his Fitzroy strip, contesting a mark in a training session with Ballarat’s Howard 'Plugger' Lockett, father of the great Tony Lockett, and (right) Lovett in his playing days. (Photos: Supplied)

I am very heartened that there are rules preventing racial intolerance now, but today they wouldn’t know what prejudice was.

I’ve had a tough life but I got through it – and I’m a great believer that history’s history, I can’t do anything about it and it’s all in the past.

I go to bed at night and if I wake up I’ve got another day to live. That’s the way I live now and I keep it simple.